Le modeste bousier semble peu probable comme candidat au statut sacré. Pourtant, pendant plus de deux mille ans, les Égyptiens en ont ciselé l’effigie dans la pierre, la faïence et les matériaux précieux — le portant, l’ensevelissant avec leurs morts et l’utilisant pour sceller leurs documents les plus importants.

Le Lien Solaire

La sainteté du scarabée découle de l’observation. Les Égyptiens regardaient le bousier rouler sa boule de bouse à travers le sable et voyaient un parallèle cosmique : tout comme le coléoptère poussait sa sphère, un coléoptère divin devait pousser le soleil à travers le ciel.

Ce dieu-coléoptère était Khepri, l’aspect matinal du dieu soleil Rê. Son nom dérive de kheper — « venir à l’existence ». Le scarabée représentait non seulement le soleil mais la transformation elle-même : le processus mystérieux par lequel la vie émerge de ce qui semble être le néant (les larves éclose de la boule de bouse faisaient écho à ce thème).

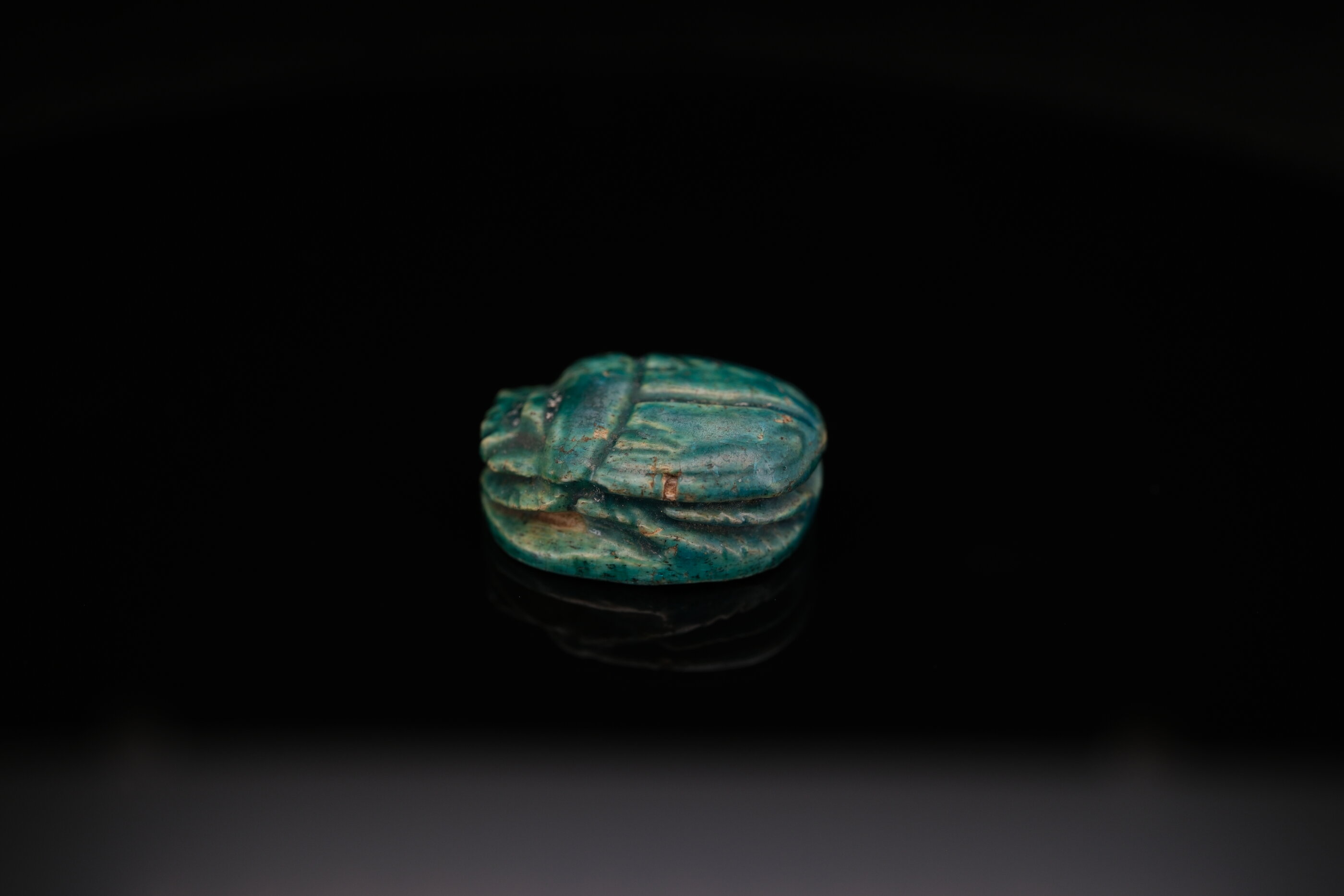

Anatomie d’un Scarabée

Le Dos

Un scarabée bien sculpté montre une précision anatomique :

- Tête : Le clypeus (bouclier céphalique) avec ses encoches distinctives

- Prothorax : Le segment derrière la tête, souvent marqué de lignes incisées

- Élytres : Les étuis des ailes, divisés par une ligne centrale

- Pattes : Parfois indiquées sur les côtés, parfois omises

La qualité varie énormément. Les pièces des ateliers royaux montrent un détail naturaliste ; les amulettes produites en masse peuvent être schématiques au mieux.

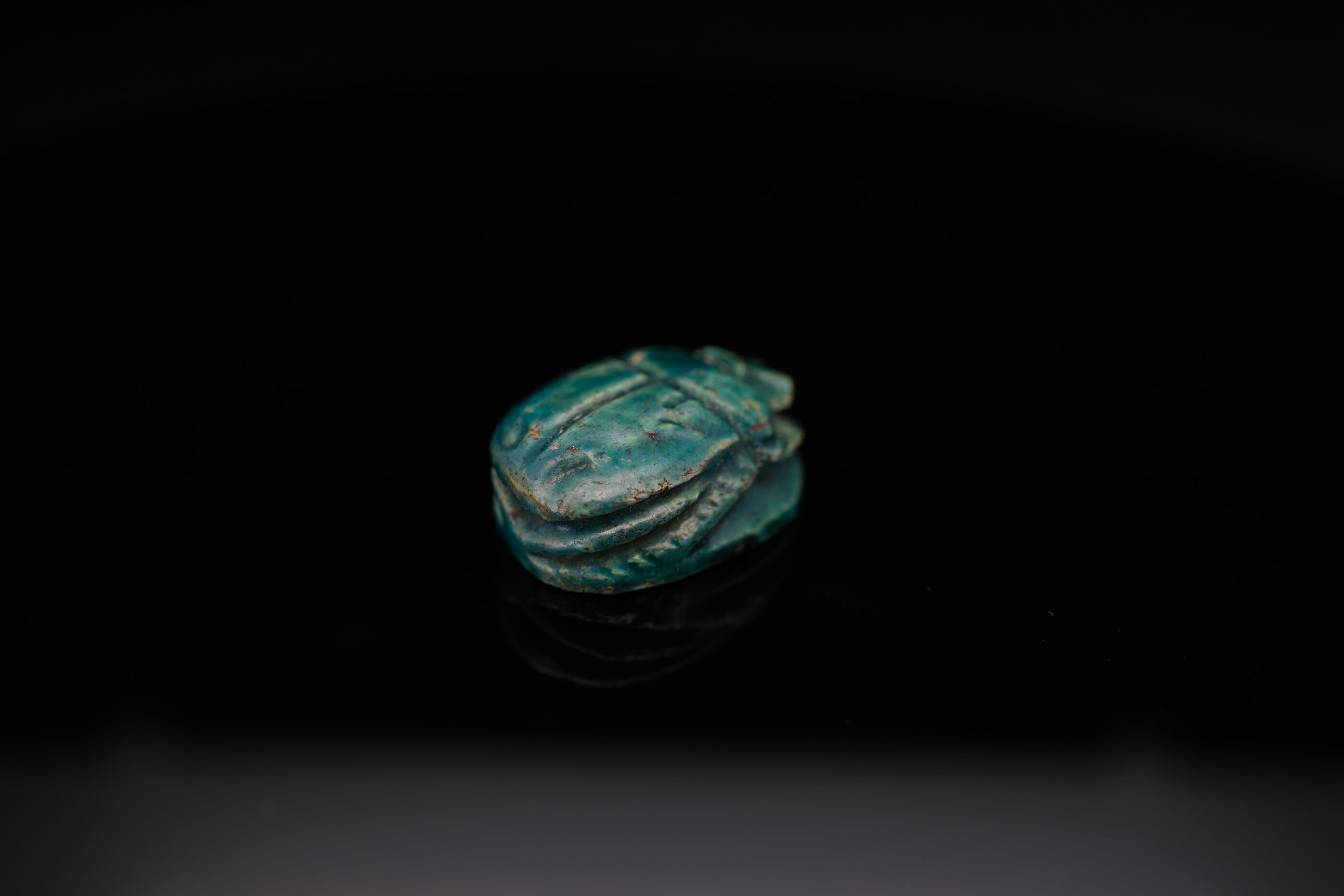

La Base

La face plate inférieure est où réside le sens. Les bases peuvent présenter :

- Noms royaux : Cartouches de pharaons (authentiques ou commémoratifs)

- Noms divins : Amon-Rê, Thot, Ptah — invoquant la protection

- Phrases de bonne fortune : nfr (bon), ꜥnḫ (vie), wḏꜣ (prospérité)

- Motifs géométriques : Spirales, volutes et designs abstraits

- Scènes figuratives : Dieux, animaux, rébus hiéroglyphiques

Lire les Inscriptions

Les bases hiéroglyphiques nécessitent un décodage. Les éléments courants incluent :

| Symbole | Signification |

|---|---|

| Plumes d’autruche | Amon, roi des dieux |

| Disque solaire | Rê, le dieu soleil |

| Figure assise | Déterminatif divin |

| Sceptre was | Pouvoir divin |

| Ankh | Vie |

| Pilier djed | Stabilité, Osiris |

Un scarabée Amon-Rê — comme l’exemple en faïence de cette collection — combine le dieu caché Amon avec le soleil visible Rê. Cette fusion théologique a dominé le Nouvel Empire (v. 1550-1070 av. J.-C.), rendant les scarabées Amon-Rê extrêmement courants de cette période.

Dater les Scarabées par Style

Les styles de scarabées ont évolué au cours de la longue histoire de l’Égypte :

Moyen Empire (v. 2055-1650 av. J.-C.)

- Formes de coléoptères naturalistes

- Motifs de spirales et de volutes courants

- Émergence des scarabées à nom royal

Deuxième Période Intermédiaire (v. 1650-1550 av. J.-C.)

- Scarabées de la période hyksôs avec motifs distinctifs

- Scarabées Anra (motifs géométriques répétitifs)

- Gravure souvent plus grossière

Nouvel Empire (v. 1550-1070 av. J.-C.)

- Apogée de la production de scarabées

- Designs de base détaillés et variés

- Scarabées commémoratifs royaux (série de la chasse au lion d’Aménophis III)

- Forte imagerie d’Amon-Rê

Basse Époque (v. 664-332 av. J.-C.)

- Styles d’archaïsme

- Gravure plus schématique

- Production continue jusqu’à l’époque ptolémaïque

Matériaux et Fabrication

Faïence

La plupart des scarabées survivants sont en faïence — une céramique émaillée faite de quartz broyé, de chaux et d’alcalis. La couleur bleu-vert caractéristique (due aux composés de cuivre) évoquait à la fois le Nil et le ciel. La faïence était relativement bon marché à produire, permettant une fabrication en masse.

Pierre

Les pierres plus dures indiquaient un statut plus élevé :

- Stéatite : Pierre tendre, facile à sculpter, souvent émaillée

- Serpentine : Vert-noir, populaire au Moyen Empire

- Cornaline : Orange-rouge, associée au sang et à la vitalité

- Lapis-lazuli : Bleu profond, importation coûteuse d’Afghanistan

- Jaspe : Diverses couleurs, chargées symboliquement

Matériaux Précieux

Les scarabées royaux et d’élite pouvaient être sculptés dans l’or, l’argent ou l’électrum, parfois avec des ailes incrustées de verre ou de pierre.

Fonction et Utilisation

Les scarabées servaient plusieurs objectifs qui se chevauchaient :

Amulettes

Portés en colliers, bracelets ou bagues, les scarabées fournissaient une protection magique. La symbolique solaire assurait le renouvellement quotidien ; les noms divins inscrits invoquaient la faveur de dieux spécifiques.

Sceaux

La base sculptée faisait également office de sceau. Pressée dans de l’argile humide ou de la cire, elle laissait une impression distinctive — utile pour sécuriser les documents, les jarres et les portes. Cette fonction explique la base plate et la popularité des designs uniques.

Objets Funéraires

Les scarabées de cœur, placés sur la poitrine de la momie, étaient inscrits du Chapitre 30B du Livre des Morts — un sortilège pour empêcher le cœur de témoigner contre le défunt au jugement. Ceux-ci sont généralement plus grands et faits de pierre sombre.

Considérations de Collection

Authenticité

Les faux abondent. Les signes d’alerte incluent :

- Marques d’outils modernes (trop régulières, trop nettes)

- Combinaisons anachroniques (mauvaise divinité pour la période)

- Condition suspectement parfaite

- Cassures fraîches avec vieillissement artificiel

L’usure authentique montre un adoucissement progressif des bords, pas une abrasion mécanique.

État

L’usure de surface est normale. Ce qui compte :

- L’inscription est-elle lisible ?

- La forme du coléoptère est-elle intacte ?

- L’émail survit-il (pour la faïence) ?

- Y a-t-il des éclats, des fissures ou des réparations ?

Provenance

Un historique de collection documenté ajoute de la légitimité. Le marché des antiquités égyptiennes a des dimensions juridiques complexes — les anciennes collections avec une documentation claire commandent des primes.

L’Attrait Durable

Les scarabées compressent une signification énorme dans de minuscules objets. Une pièce de faïence de deux centimètres pourrait encoder la théologie solaire, l’identité personnelle, la protection divine et la fonction pratique — le tout dans une forme assez élégante pour être portée quotidiennement et assez puissante pour accompagner les morts dans l’éternité.

C’est un design efficace. Les Égyptiens comprenaient le branding trois millénaires avant Madison Avenue.